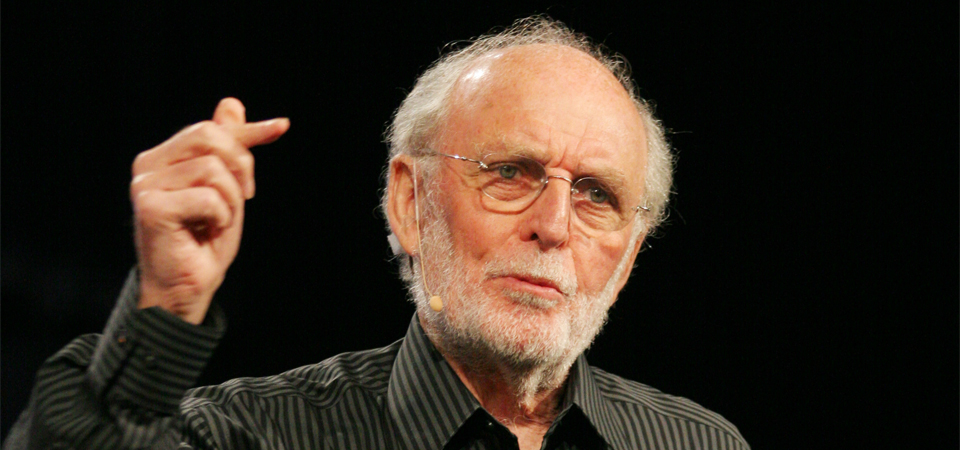

an article by Stuart Briscoe

Gerald Griffith, a pastor and Bible teacher in Toronto and my good friend, one day said to me, “Every week God gives me bread for his people.”

I looked him straight in the eye and replied, “That’s true, but you spend a lot of time in the kitchen!”

He had to agree.

Those hours “in the kitchen” are among the most important of my week. Why? Because in the kitchen I prepare what God gives me to feed his people. And they can be picky eaters.

People are distracted by all kinds of things–legitimate things, for the most part, but sometimes not. Pain fills a lot of hearts. People are unhappy at work. Or their homes are less than ideal. Or they feel great economic stress. Or they strain under the demands of a job. When troubled people come to church, their thoughts suppress the appetite for God’s menu. My job as a preacher is to overwhelm the careworn with the aroma of the gospel.

So when I preach, I’m continually thinking, How am I going to hold and use the attention so tenuously lent me? I don’t have it long. When I listen in on conversations in the church foyer any Sunday, I’m amazed at how quickly thoughts skirt from divine worship to talk about the Bucks and the Brewers, or making a buck and what’s brewing in politics. So one of my major responsibilities of the week is to grab their attention with the sermon.

Consequently, I pass my sermon material through what I call the “So what?” test for relevance. There’s no problem with the Scriptures. They’re relevant. But I have to do my part to make the sermon as relevant as the Scriptures, because I want people to leave saying, “I see!” and not “So what?”

The way to do that, I’ve found, is to preach to the mind, the will, and the emotions. Donald English once said: “When I leave a church service, I ask myself the question: Which part of me need I not have brought here today?” That’s why I try to touch every part of the person through the material I use in the sermon. If I’m preaching to mind, will, and emotions, people won’t go away saying, “So what?”

Preaching to the Mind

Theology challenges the mind. I admit not many people think in theological terms. Perhaps that’s the problem: they haven’t looked at the worldview – the philosophy of life – behind their lifestyles. So I intend to keep them thinking about it when I preach.

For instance, I often point out the flip side of a proposition or belief. Most issues have at least two sides, so when I make a strong point about something, I’m anxious to point out that others believe differently. Often I’ll spell out the opposing beliefs. I’m not being wishy-washy, but getting people to think. Those with tunnel vision need someone to open up for them a broader view.

Once I was preaching a series on the Apostles’ Creed: “I believe in God the Father Almighty . . .” To get at the opening phrase fully, I stepped back and tried to help my congregation understand why the concept of God as Father disturbs many in our society. How does the radical feminist feel? I’d done my reading on the matter, so I quoted some feminists. I also mentioned those people who have been abused by their fathers. For them, unlike many of us, father does not have good connotations.

If we have a high view of Scripture and God, I continued, we have to beware of inflating images of our fathers to explain God; otherwise we will be left with a heavenly Father with ballooned faults. When we say “God the Father,” I concluded, we surely mean something more figurative and less literal than a polished-up version of our dads. I wanted people to accept the transcendent concept of God that Scripture communicates by the term Father.

I try to stretch people through my preaching. I did that in the Apostles’ Creed series when I preached on “Maker of heaven and earth.” Most people in our society view the universe as a closed system operating on set laws that are empirically discernible. So where does a “Maker of heaven, and earth” fit in? Because materialists and naturalists populate our society, I found it necessary to explore an alternative to a closed system. By preaching good, hard science and theoretical physics along with sound theology, I was able to capture their attention.

Our access to people’s minds is a terrible thing to waste, so I try to engage the mind. When I can snag their thinking and broaden their understanding, I’ve wrested their attention for the gospel.

Preaching to the Will

When I preach to the will, I’m looking for response. I want people to act on what is said. As a pastor, I’m apt to be gentler and less demanding than I might be as an itinerant preacher, because I’m going to be with the people for many years. I don’t need to get all or nothing in one shot.

I’m usually looking for minor movement in the right direction, rather than a gargantuan step. It seems that people’s wills move incrementally. So I try to choose words and illustrations that encourage movement, even if slight, in the right direction.

I use the word encourage purposefully. Usually people respond better to encouragement than to “challenge.” Most people need inspiration and courage more than a kick in the pants. So I try to give people bite-sized and good-tasting pieces to chew on.

For instance, when I preached on “By this shall all men know that you’re my disciples, that you love one another,” I didn’t instruct people to go out and swamp their world with love. Instead, I said, “Think of one person close to you. How well do you love that person in light of what we’ve talked about today? If agape love is concerned primarily with the well-being of others, irrespective of their reaction, then practice that love this week. See if your love makes any difference.”

When I preach an evangelistic sermon to the will, I want people to understand that repentance might be a simple step rather than a big leap, but it nonetheless needs to be ventured.

A woman wanted her pastor to pray with her because she no longer felt Christ’s presence. When he asked about her problem, she said, “I don’t want to talk about it. Just pray for me. That’s all I want of you.”

He probed gently anyway, and eventually she began to cry: “I’m living with my boyfriend, and I really have no intention of moving out.” She wanted to sense Christ’s presence while she lived in disobedience. She needed to repent, of course, and end the disobedience if she were to feel close to God again. Without that step of the will, her spiritual life would remain stale.

The will is a wily creature. Sometimes it needs to be encouraged, sometimes challenged. The trick to preaching to the will is to find which kind of stimulation best works for the people to whom you’re preaching.

Preaching to the Emotions

A while back, I was preaching about Christ being rejected. Such a familiar theme is prime material for a yawner of a sermon. So how did I add interest? Emotions.

I told the story of Winston Churchill’s post-war experiences. I’m a Churchill fan, and I recalled his tremendous impact during the Second World War. I said as a little boy I listened on a crackling radio to his famous speech – “We will fight them on the beaches…. We will never surrender!” All the time bombs were dropping, and the sound of anti-aircraft guns and the glare of searchlights split the night. His bulldog-like determination got us through that dreadful period.

Churchill was the man of the hour during the war. But at the end of the war, an election was held, and, surprisingly, Churchill lost. After all he had done, the British people turned him out of office.

The congregation looked shocked when I reminded them of that bit of history. Then, very quietly, I said, “He was a broken man.” I just left it there for a moment. While that thought stirred within them, they felt deeply what rejection means.

I’d engaged their emotions. Churchill’s rejection really bothered them. From there it was a short step to move those feelings to the rejection of Jesus Christ.

Some rightly object that we can address the emotions at the expense of the mind, but that’s not my problem. I’m not as prone to manipulate people’s emotions as I am to forget them. Purely intellectual matter can get extraordinarily dry, but emotions add life. Emotions move people to response. People identify with them.

Humor, because it elicits emotion, plays an important part in my preaching. Humor can be a wonderful servant or a dreadful master. But if Philip Brooks’s definition of preaching is right – that preaching is truth communicated through personality – then I need to communicate through humor, because I enjoy humor.

A fellow once said to me, “I’ve been listening to you for quite a long time now, and sometimes when I go home from church, I find a knife stuck in my ribs. I always wonder, How did he do that? So today I decided to watch you closely, and I found out how you did it. You got me laughing, and while I was laughing, you slipped the point home.”

He wasn’t suggesting that I was manipulative. Instead, it was a warm-hearted compliment. He was saying that humor puts us off guard, and at those times we are highly receptive to penetration by the Word.

Once in a sermon I spoke about a purported memo written to Jesus by a management consultant. It evaluated the aptitude of the various disciples. Predictably, it panned the qualifications of most of the disciples – too unrefined, no credentials – but it lauded the great potential of one: Judas. People laughed. They could feel the irony. In a humorous way, I made my point: the unrefined and ill-qualified disciples were transformed into sterling men of character by the Resurrection.

Humor also allows the mental equivalent of a seventh-inning stretch in a sermon. People’s minds need a break now and then, and humor can supply it in a way that enhances the sermon. After momentary laughter, people are ready for more content. Or when something disturbs the sermon – such as a loud sneeze – a good-humored retort can bring attention back to the preacher.

Fear also can be used for good or bad. I hesitate to motivate people with fear. I would rather love be their motivation. Fear, however, can be used to bring interest to well-worn passages, for fear grabs people.

When preaching about the security that the presence of the Friend brings, I recalled an invitation to speak at pastors’ conferences in Poland. When I arrived at the Warsaw airport, nobody came forward to greet me. I had no names to contact, no addresses, no phone numbers, no Polish money. So I just stood in the middle of the airport while people collected their bags and the lobby emptied. Soon workers began to close down the area, and I was left standing there very alone.

My loneliness turned to fear when I heard a voice behind me say “Briscoe.” I turned to see a fellow in a long, leather coat, the type I’d seen in too many potboilers about the Second World War. I thought, ‘Hey, don’t look at me! I didn’t want to come here in the first place!’ But before my panic was unleashed, he came over, grabbed me, kissed me, and said warmly, “Brother Briscoe!” Then he leaned over and said, “Quickly, we must get on the tram car,” and we rushed to catch it.

On the tram he told me, “Speak loudly of Jesus. You can use English and any German you know. They’ll understand.” And so as we hung on the straps in that tram, I began to broadcast my love of Jesus, and everybody started to listen. Suddenly I was enjoying myself. The difference between being lonely and afraid a few minutes before and being comfortable on the tram was this: a friend was with me. I used fear that was transformed into fun to illustrate Jesus’ words: “I am with you always, even to the end of the age.” As people felt my fear, they hooked into the relief Jesus brings.

If I don’t preach to the emotions, I’m missing a good part of the person sitting in the pew. Since people bring that part of themselves to church, the least I can do is address it with my sermon.

Being an Interesting Preacher

There is far more Bible to preach than I ever can cover in one lifetime, so I’ve never felt preached out. But I do hit dry spots in my preaching. Sometimes when I’ve been in a series for a while, I think, ‘Boy, this is pretty dry. Let’s get out of here quickly and keep the damage to the minimum!’

At such times I ask myself, ‘Is there something wrong with me personally? Maybe I’m tired. Maybe I need refreshment. Maybe other things are on my mind.’ Often I find a half-hour nap can solve my short-term problem.

I also ask myself, Am I not grappling with the biblical material? Have I, perhaps, written it off subconsciously as uninteresting? Maybe I haven’t taken my subject seriously. That is bound to make it dull, to both preacher and listener. If so, I need to work harder to find a refreshing, unique angle. When I discover a provocative aspect of a text, I find it easier to interest people in what I have to say. In terms of the bigger picture, if I expect to fill my sermons with interest year after year, I need to keep my mind interesting. And that’s a continuing task for any preacher.

Ideas stimulate me. I love to talk to people when I start to become stale. I may discuss deep theology with fellow staff members or sit down with a Green Bay Packer linebacker and talk about how long it takes him to recover physically after a game or a season. I find it all interesting and stimulating.

Conversations keep me excited about people and life and faith. They also provide ways to add interest to sermons, because they keep me current. About once a month on a Sunday evening, Jill and I invite a dozen or so people to our home for a quiet evening of coffee, dessert, and conversation. I simply draw people out and let them talk about what interests them. I love to hear where they are coming from, what excites them, what they are talking about.

Often the conversations cross-fertilize. One time when a judge and a professor of medical ethics sat beside each other, the conversation turned to abortion. The professor had done some research on those who ran the abortion clinics in Milwaukee. He was concerned about medical ethics. The judge came at it from his long experience dealing with welfare families. The ensuing conversation enriched us all.

What I find interesting doesn’t always get the same vote from my congregation. For instance, my taste in music doesn’t mirror the congregation’s, and although I’m greatly interested in European history, most people couldn’t care less about it. In addition, I’m a man with not untypical masculine tastes, and, naturally, many of my parishioners are female. So I simply can’t assume my tastes, my interests, are the norm.

Therefore, I must think about what interests others. That prospect doesn’t intimidate me as it might when I consider that over the years I’ve been able to understand the tastes of my wife and children. I just have to keep my ears open to learn what’s interesting to people who aren’t exactly like me.

Or keep my eyes open. When I’m on an airplane, I confess, I often thumb through a copy of Glamour or Ms. Sometimes I find powerful and well-written articles that give me a window into the secular mind. I often take notes. Part of staying in touch with interesting material is exposing myself to secular thinking and trying to see what the world considers interesting. Just being interested in life produces most of the illustrations I use.

In short, I’m prepared to be interested in what other people find interesting. I don’t have to agree. I don’t have to buy it wholesale. But it’s to my advantage to understand people’s interests and speak their language. I need to know what’s going on in others if I am to say anything interesting to them.

When you get right down to it, preaching is like farming. I often say, “Lord, here I am. As far as I can tell, I’ve tried to fill my sack with good seed. I’ve done my homework, I think my attitude is right, and it’s the best, most interesting seed I’ve got. I’m going to scatter it now, Lord, so here goes. We’ll see what comes up in the field.” Then, once I’ve sown the seed, I do what farmers do: I go home and rest.

Over time, I get to watch that seed sprout and grow. A lot depends on the soil. God has to give the seed life. But eventually, I see the results of the good seed I’ve sown.